Issue Two

December 2024

The Sunday School Room

Karen Arnold

Childhood is filled with ritual. Tiny chants and spells to keep fear at bay, to impose order on a world, where truth is slippery and rules don't make any sense. It was a summer of changing bodies and restless thoughts. A summer when the country was obsessed with rain, hosepipes were banned and stories about dowsing and rain dancing ended the local evening news programmes. We developed strange obsessions, wouldn't tread on pavement cracks, spat at magpies and drove our mothers insane with our need to sleep with the light on, filling the room with the lazy flap of moth wings stirring the hot night air before crashing against lampshades, drunk on 40-watt light. We terrified each other with tales of horror films covertly watched through the bannisters after bedtime, inventing our own folk lore of metal and demolition, blank eyed deserted factories and shadowy boarded up buildings. No one expects to find ghosts in a small, shabby, Black Country town, a place left behind like sea coal when the tide of heavy industry went out, but we were steeped in haunting and loss.

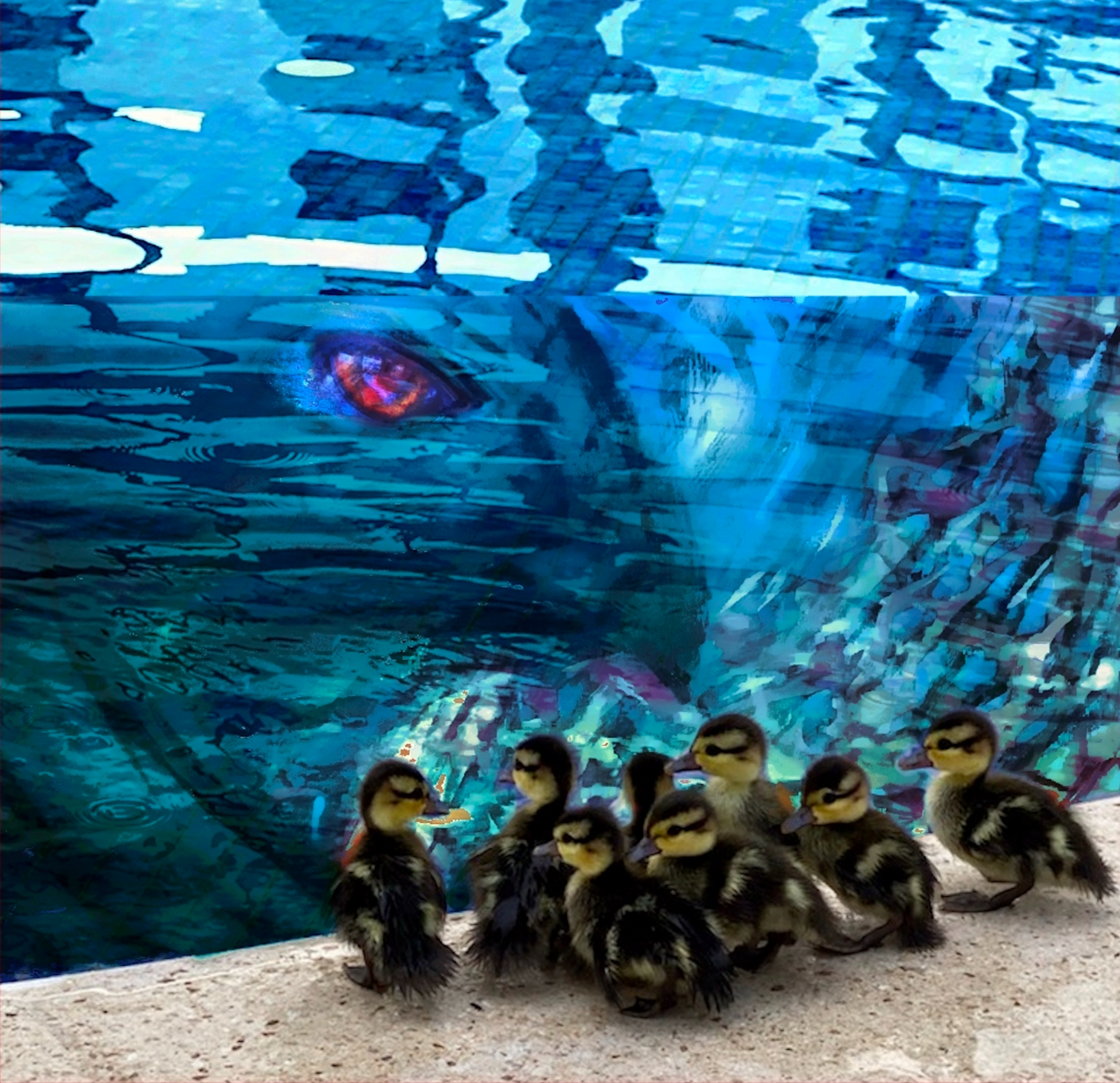

Unholy Visitation: original artwork by Anne Anthony

The chapel was unremarkable, a small white building with green painted double doors and window frames. Even the whitewashed walls had taken on a patina of green as lichen and moss had started to stake a claim. It was not the gothic mansion of the Friday night Hammer Horror. It sat square in the middle of a residential street of ordinary Edwardian terraced houses, utilitarian, lonely and unloved.

We couldn’t’ remember the last time a service had been held there. We eavesdropped on grown up conversations from our vantage points behind hedges and garden gates, we worked out that the last thing to take place there had been a Sunday school anniversary, before it’s sudden closure, the congregation moving away to join the chapel in the next town. Our parents would fall silent the moment they saw us, shaking their heads. We were told stay away. It was a match that set fire set to petrol-soaked imaginations and the chapel called to us like a siren.

We were organised by the same natural phenomena that tells swallows when to migrate or teaches blue tits how to peck holes in milk bottles. A gang of children gathered in the street. A wordless signal shimmered between us and, like salmon swimming upstream, we found ourselves in the scrubby, overgrown patch of land that lay behind its flimsy iron railings.

Behind purple spires of rosebay willowherb we found an old mattress, stained and repellent. We could not voice the ripple of revulsion stirred up by the brown stains and ripped ticking. Pages from old magazines lay scattered on the grass, pictures we did not understand, but which we all knew should not be mentioned to our grown-ups.

Each day we became bolder, climbing the crumbling steps to the front door, scrambling to gain a toe hold on the wall to see into the windows, catching a tantalising glimpse of pews and scattered books, a whiff of damp and something else. something rotten.

With the heat of summer slipping into September, we were desperate to avoid any thought of returning to school. We gathered outside the chapel for one last assault. A panel of the door had become waterlogged and rotten. We took it in turns to kick at it until a hole appeared, big enough for the smallest member of our gang to fit a hand through and lift the bar holding the door shut.

The door creaked open, and we peered inside. The light was dim, filtered through the trees growing against the window. The smell was stronger now, a musty mix of damp paper mixed with something sweet and dreadful. It was silent, apart from a steady drip of water. There was a small stage, still filled with little chairs.

We looked at each other, too scared to walk further in, too stubborn to go back. We shoved Gary over the threshold ahead of us, and he yelped with alarm. He stumbled into the chapel, falling face first onto the floor, his outstretched hand landing on the rotting carcass of a pigeon, sending maggoty flesh and stinking fluid across the floor. We stood around him as he wailed, frantically scraping the slimy mess from his hands on the wiry brown floor tiles. We watched, reluctant to help him, embarrassed and ashamed of his noisy tears.

I moved away from him, calling the others to look at the motley pile of left behinds, a blue cloche hat that I tried on, pirouetting around in it until I remembered my mother's dire warnings about nits and hurled it down the aisle. The mounds of hymn books swollen and mouldy, soaked by the water that had trickled in from the broken guttering leaving a brown and yellow tear stain on the wall.

A pair of red sandals. Something abandoned and terrible in its smallness. Something that made us want our mothers with a terrible, aching need in the centre of our chest. A shaft of sunlight like a spotlight on an absence we did not want to see.

There was an explosion of noise, furniture clattering and shrill childish screaming, as we ran. Feet slipping and skidding on the mess of maggots and pigeon corpse, we grabbed at each other’s hands desperate not to be the last one out, the one who got stuck in the hole in the door.

We didn’t look back and we didn’t stop. We never spoke of what we had seen, On the day the demolition men came, we stood hand in hand watching with hot dry eyes until every stone was torn down.

About the author

Karen Arnold

Karen Arnold is a writer and child psychotherapist. She came to writing later in life, but is busy making up for lost time. She is fascinated by the way we use narratives and storytelling to make sense of our human experience. She won the Mslexia prize for flash fiction in 2022 and was placed second in the Oxford Flash Fiction competition in 2023 She has work in The Waxed Lemon, The Martello, and Roi Faineant amongst others.

She can be found on twitter @aroomofonesown_4